In My Own Little Corner

Willie Little

5 August – 2 October 2022

Curated by Blake Shell

Photos by Mario Gallucci

Gallery Guide

Oregon Contemporary presents In My Own Little Corner, a solo exhibition by Willie Little. In My Own Little Corner is the third and final exhibition in our large-scale program Site, a series of exhibitions by Oregon artists replacing the Portland2021 Biennial. The exhibition is a multimedia, interactive installation consisting of a series of vignettes from the artist's hometown near Little Washington, NC, exposing the often untold stories from a rural Black child's perspective while revealing the universality of the inner turmoil many gay children experience.

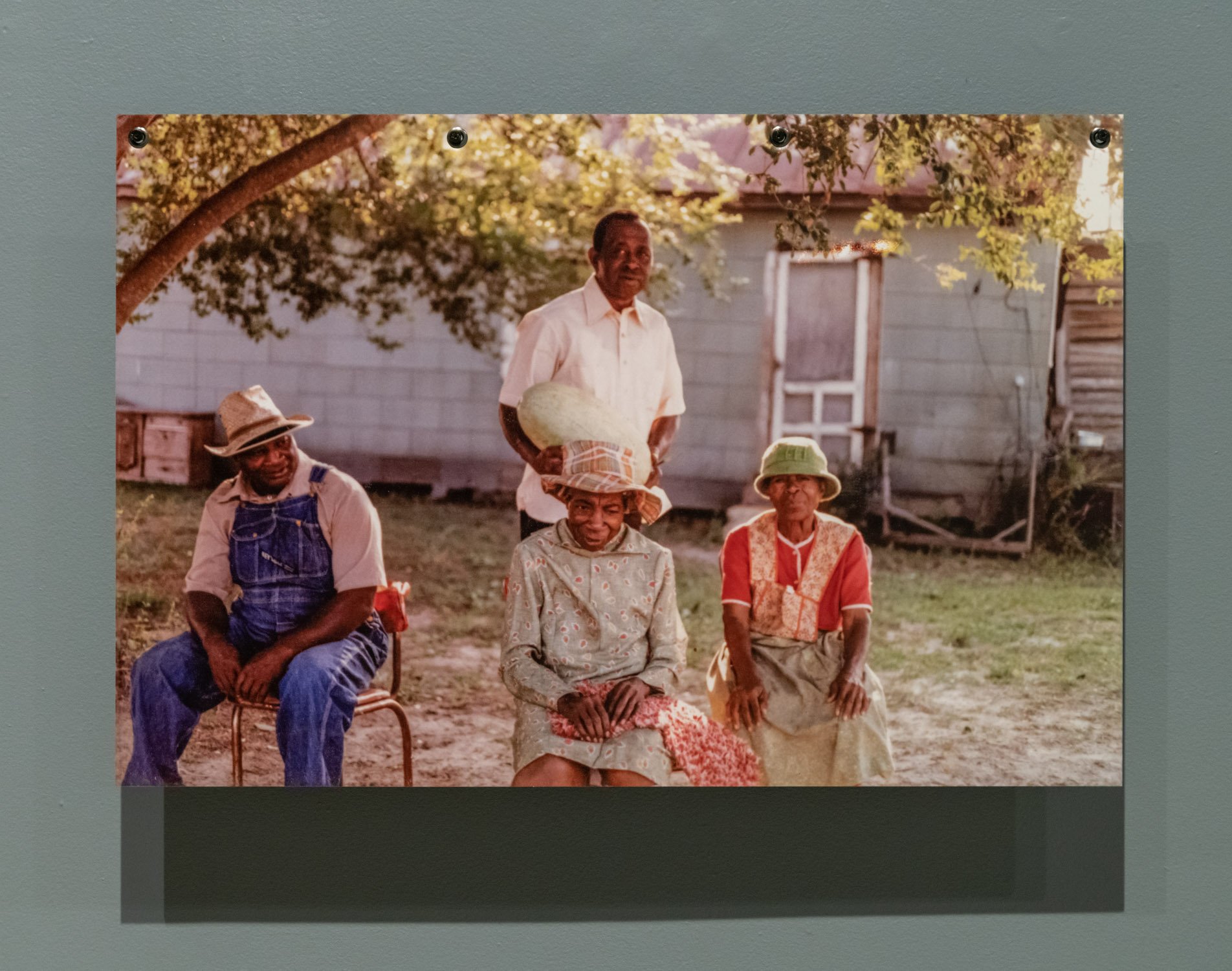

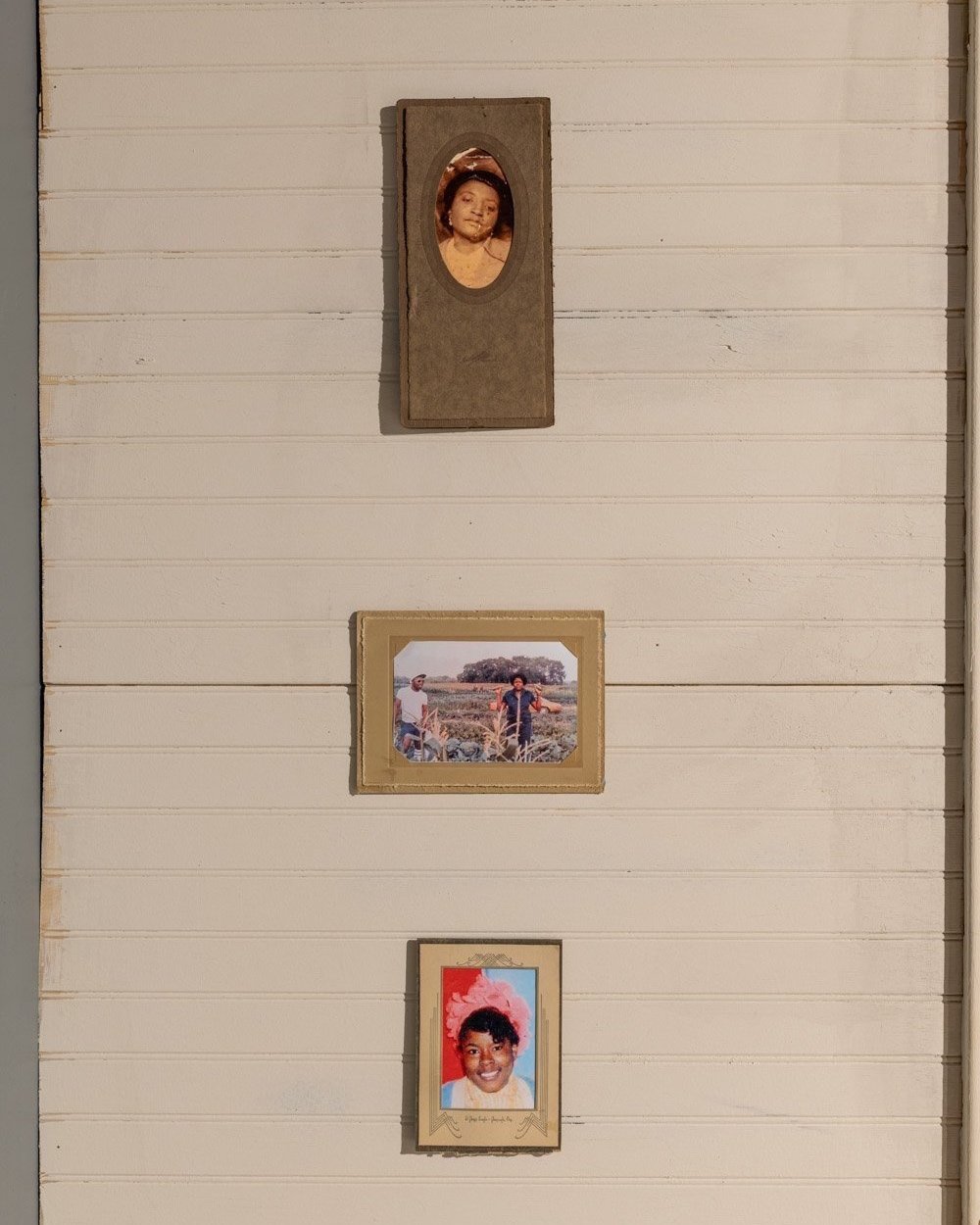

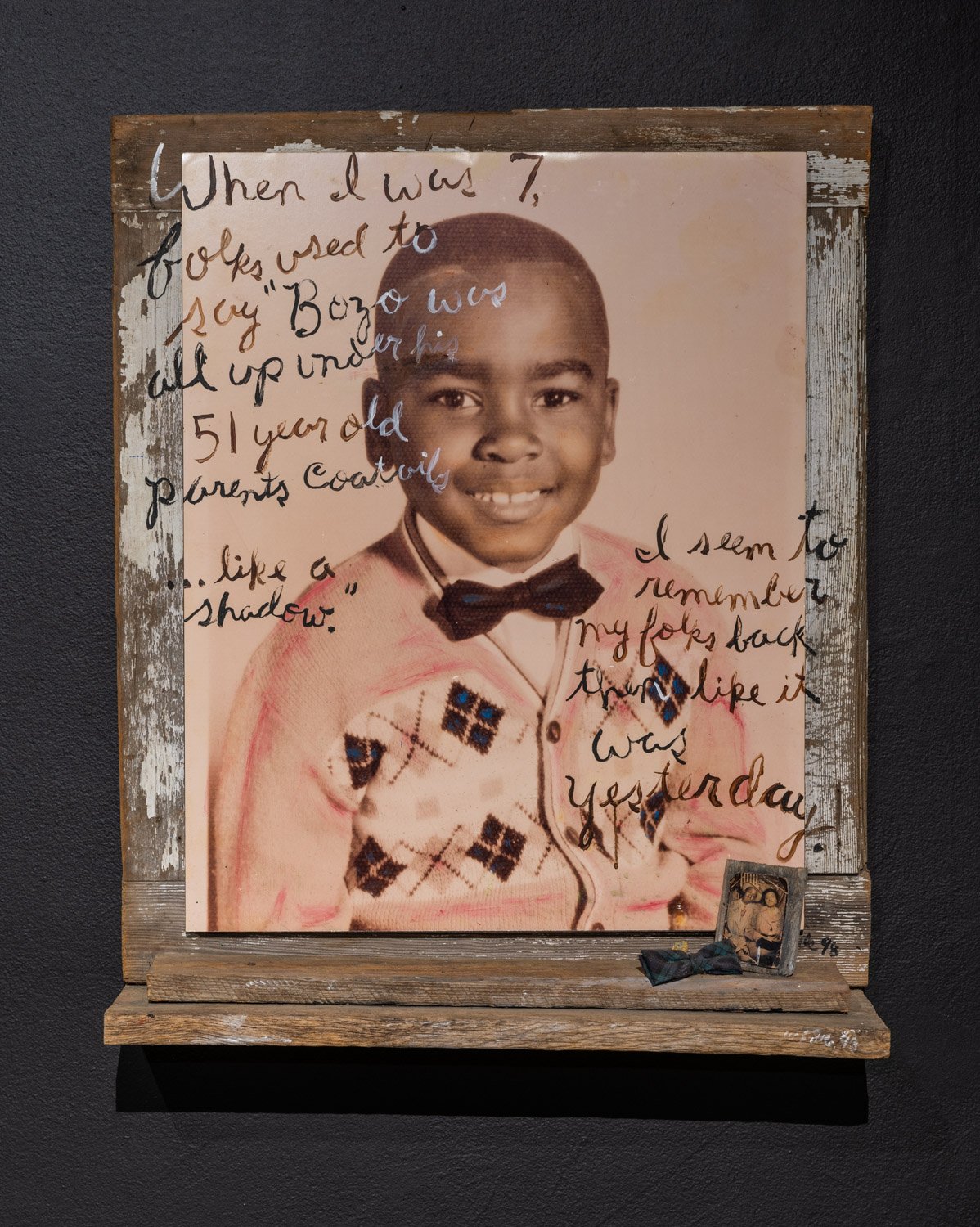

The title, In My Own Little Corner, is taken from Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella: “In my own little corner, in my own little chair, I would be whatever I want to be....” The installation invites the viewer to experience the world of the imagination of a young, Black, gay boy from rural North Carolina. The installation includes theater walls, found objects and photographs and a sound environment lifted from the pages of Little’s recent memoir/ art book, In the Sticks. These vignettes are tableaus that transport the viewer to a time and place from his past – through sight, sound, and found objects. They reveal some of the artist’s dreams, conflicts, and uncertainty he experienced as an imaginative and sensitive boy from Pactolus, North Carolina in the 60s and 70s during a time of radical change, when Little desperately dreamed to one day get out of the sticks.

Willie Little is a Black multimedia artist and author. His visual narratives document a fading part of rural southern life while also tackling topics of racism and Black Lives Matter, Social Justice, and the childhood memories of growing up on a tobacco farm in Eastern North Carolina. Little incorporates sculpture, painting, sound installations, re-constructed architecture, recycled memorabilia, and real-life stories. The common thread in all the work he creates is his examination of the manifestations of physical and societal decay in American culture. Little's solo exhibits include the Smithsonian Institution, the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University, the American Jazz Museum and Noel Gallery. He currently resides in the San Francisco Bay area and Portland, Oregon.

In My Own Little Corner is generously supported by Oregon Community Foundation’s Creative Heights initiative and the Fred W. Fields Fund of Oregon Community Foundation. Oregon Contemporary is also supported by The Ford Family, Foundation, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Robert & Mercedes Eichholz Foundation, VIA Art Fund and Wagner Foundation, the Maybelle Clark Macdonald Fund, the James F. & Marion L. Miller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Oregon Arts Commission, and the Regional Arts & Culture Council. Other businesses and individuals provide additional support.

Commissioned essay by Ella Ray

The 1997 version of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella, starring Brandy Norwood as the title character and Whitney Houston as her Fairy Godmother, is a noteworthy reimagining of the original 1957 film and its 1965 remake. While this iteration of the production adheres to the canonical structure of the tale—the wicked stepmother, the pumpkin-turned-carriage, the prince, the glass slipper—its themes of transformation and desire are deepened by the protagonist’s identity as a Black girl from a working-class background. Norwood and Houston world-build together to conceive of a life beyond Cinderella’s repressive and oftentimes abusive homelife. The power of her imagination catalyzes Cinderella to move from “her own little corner in her own little room” to a life of her own creation. In a standout scene, Norwood and Houston slip into a call-and-response as they hurry to the ball, the lyric “Impossible!” slowly but fiercely becoming “It’s possible!” Nurtured by the Black gospel tradition and dripping with a R&B cadence, their voices swell with faith that their current circumstances can and will change and that the transformation is already in motion.

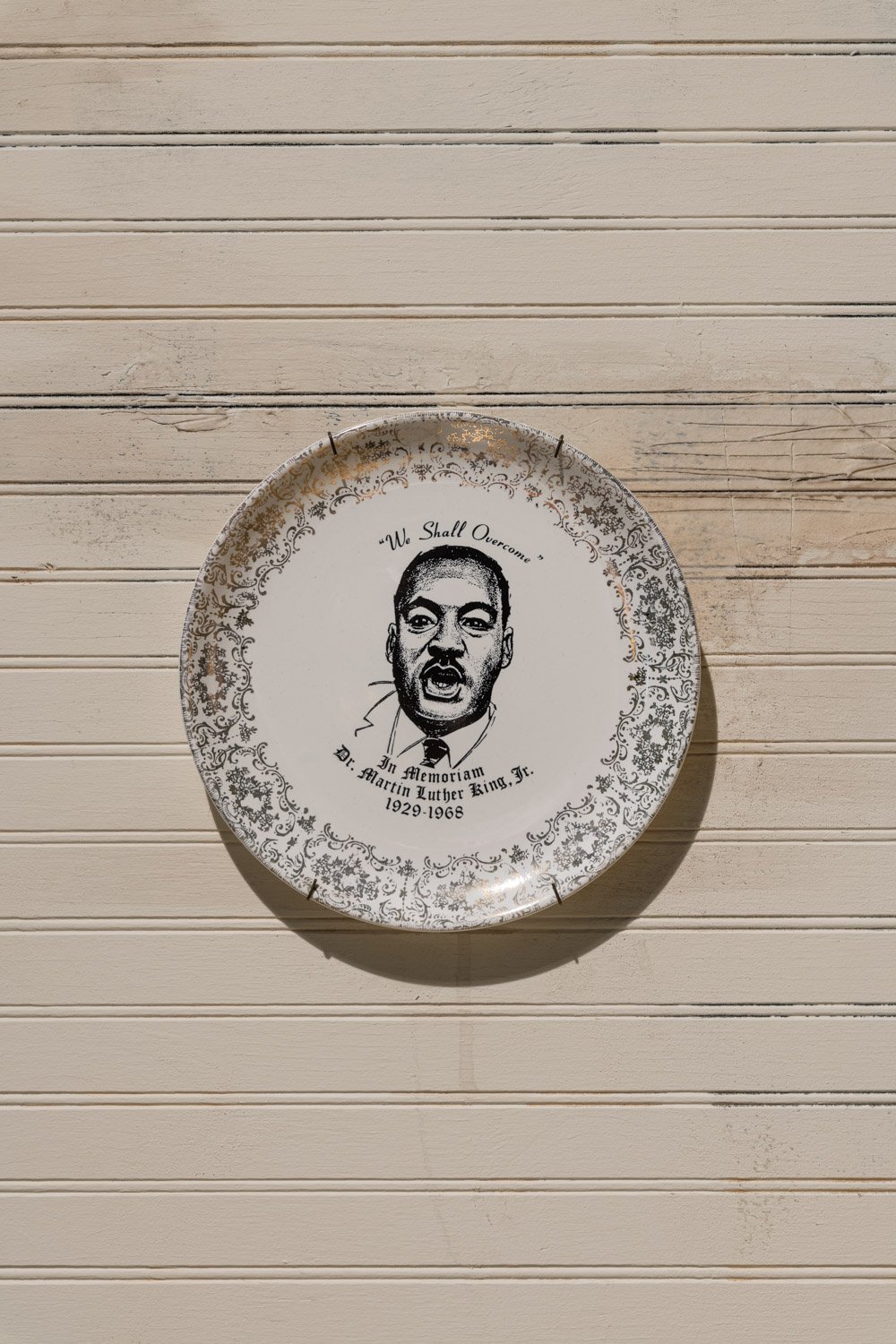

This kind of dreaming, which envisions the quotidian as a vehicle for escape, is at the core of Willie Little’s practice. Little was introduced to Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella as a child: he first resonated with Lesley Ann Warren’s 1965 performance in the title role; thirty-two years later, he was particularly affected by Norwood’s and Houston’s performances. Little sees Cinderella and her story as a reflection of his own alienation as a gay Black child raised in “the sticks” during the first years of desegregation. The objects and dreams that filled Little’s childhood bedroom eventually laid the physical and conceptual foundations of a practice that maps Black Southern vernacular aesthetics, as well as experiences of antiblack homophobia and classism. Collaging together aspects of the Black fantastical, formative iconography from popular culture and politics, and deeply biographical structures, Willie Little’s In My Own Little Corner is a multisensory assemblage that draws on his internal and external worlds over the course of his entire life and career.

In many ways this installation is a return to form. In My Own Little Corner is a to-scale recollection of Little’s childhood home in North Carolina; it uses objects, images, and sounds to whisk us out of the gallery and into the artist’s memory. Little is no stranger to rebuilding the places and spaces of his past—in 1996, he first exhibited Juke Joint, a reconstruction of his family’s hybrid grocery store/club from the 1960s, complete with a jukebox that filled the site with overheard snippets from patrons’ conversations. Later, Little’s Kinfolks (1998) reproduced his family’s tobacco farm. This installation included freshly cured tobacco leaves to sensorially transport audiences to the rural agricultural site. In My Own Little Corner relies more on the artist’s internal connection to objects than his previous works did, and focuses on how those objects informed his relationship to home and his desire to leave. We experience the Little family home, from the porch to the bedrooms, through Willie’s eyes. The wood, metal, paint, images, TV, dolls, shingles, and swing used to rebuild this home were gathered meticulously from flea markets, eBay sales, vintage shops, and neighborhood curbs that Little felt “called to.” He assembles the objects within the house in a way that emphasizes their three-dimensionality, gesturing toward Black American assemblage traditions and the haptics of that medium. And while much of Little’s source material is chosen for its likeness to things within his childhood home and imagination, the artist notes that “when objects are assembled with care and specificity, the more universal they are for the viewer.”

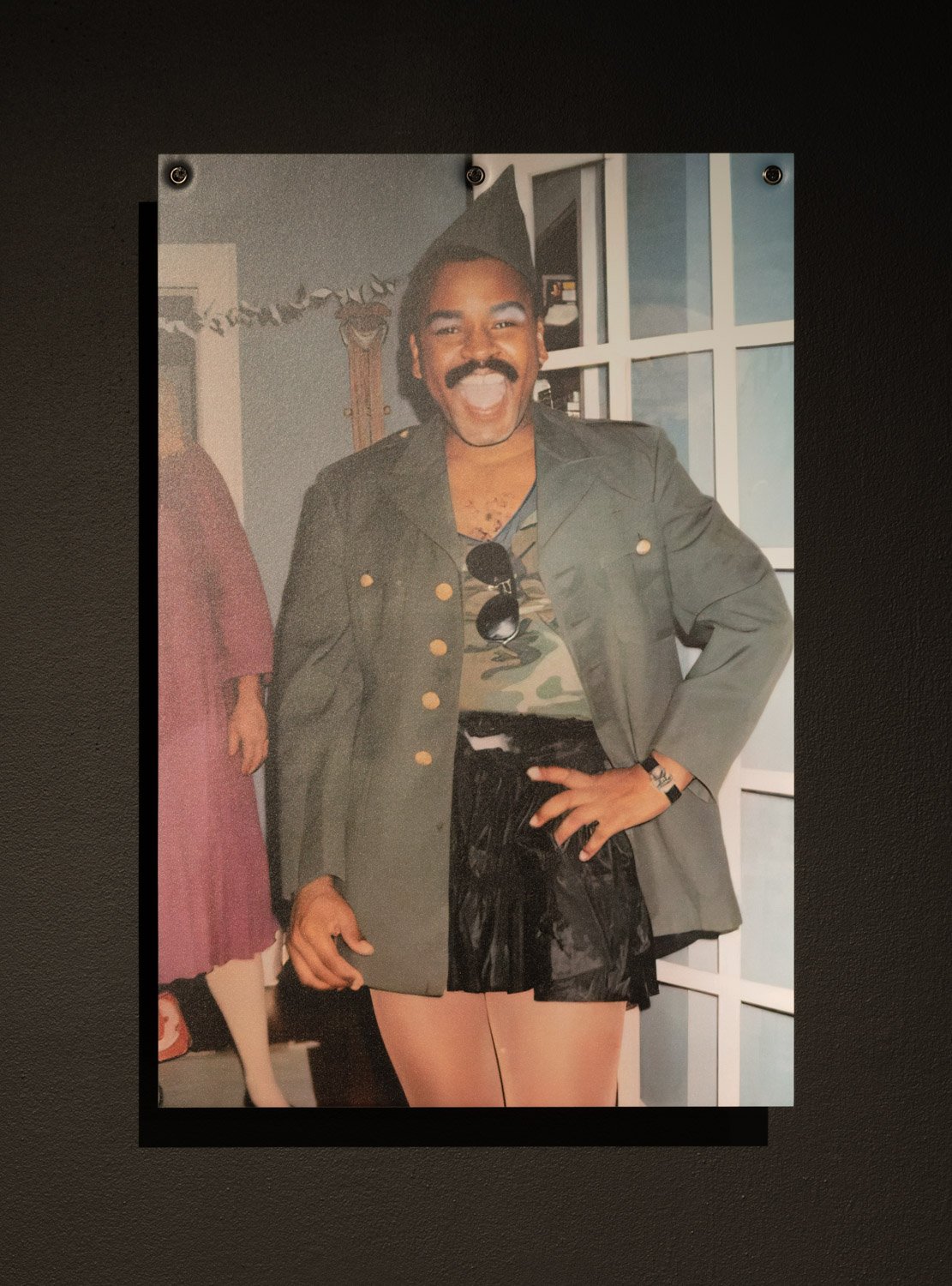

In the installation, the tension—or as Little calls it, “the angst”—between his nuclear family and himself, as a gay child within that family, is palpable. Visually, this strain is made evident through the artist’s juxtaposition of family portraits (such as the one of his father, grandmother, and aunt in front of the family home) with images of himself after he moved away (like the photo of his first time in drag as a young adult). By editing and curating images from his past, Little articulates his own version of a family history, inserting what he calls his “authentic self” into the fold. While some of the details express the pain Little correlates with home, the television can be understood as the pumpkin that took him to the ball. A nineteen-inch black-and-white TV set from the late 1960s, nearly identical to the one the artist watched as a child, is foregrounded in the space. On it, shows ranging from educational programming for children to episodes of Get Christie Love! play in loops, adding a kinetic ambience to the work. The TV is one of many objects that Little sourced himself during the earlier months of the pandemic, and it serves a great purpose in the larger narrative. “One of the most pivotal elements of this installation and of my childhood is the television. It was a portal that allowed me to see what was possible. I sat at the foot of the bed and saw that there was proof of life outside the sticks,” Little says.

In My Own Little Corner is a testament to Willie Little’s capacity to see a future for himself outside of the conditions he was born into. In conjuring a world beyond his “little corner,” the artist redefines his relationship to the most intimate space—home—and to the objects, materials, sounds, and people that both restricted him and gave him the freedom to be himself.

Ella Ray is an art historian, writer, and library-worker producing texts, objects, exhibitions, ephemera, and programs that help us reorient our understanding of art history and reflect an investment in Black feminist thought, formal and conceptual experimentation, and cross-diasporic community. After graduating from Portland State University in 2018, Ray has mounted curatorial, research, and writing based projects through and alongside KSMoCA, the Black Abbey Residency, the Portland Art Museum (by way of the Kress Interpretive Fellowship), and Portland State University. Ray made their curatorial debut in 2021 with the group show "Nobody's Fool," hosted by Carnation Contemporary. Ray’s work can be found in Variable West, Cult Classic Magazine, the Studio Museum in Harlem’s website, the Portland Art Museum’s members’ magazine, the King School Museum of Contemporary Art, ArtAboutPDX, OregonArtsWatch, and in a forthcoming Ford Family Foundation catalog.